Lessons Learned from COVID-19 about Resilience

David Marmorek

Lead Scientist | Senior Partner, ESSA Bio | in

Jimena Eyzaguirre

International Team Director | Climate Change Adaptation Lead, ESSA Bio | in

What is resilience?

In 1973, one of ESSA’s mentors, Dr. C.S. (Buzz) Holling, published a seminal paper on the Resilience and Stability of Ecological Systems (Holling 1973), which has stimulated decades of study into the resilience of ecological, social and economic systems (e.g., Gunderson and Holling 2002). Resilience has been defined many ways. One useful definition (Walker et al. 2004) is “the capacity of a system to absorb disturbance and reorganize while undergoing change so as to still retain essentially the same function, structure, identity, and feedbacks”. Holling and Gunderson (2002) comment that the challenge of resilience is “to conserve the ability to adapt to change, to be able to respond in a flexible way to uncertainty and surprise”. Resilience, the capacity to renew and reorganize after disturbance, needs to be actively managed (Yorque et al. 2002). Over the last four decades, ESSA’s environmental scientists have worked collaboratively with managers, disciplinary experts and the public on how to maintain the resilience of linked social-economic-ecosystems to various disturbances, including forestry, fishing, eutrophication, acidification, dams, invasive species, coastal development, and (ever more strongly) climate change. We are environmental scientists not epidemiologists. Our past experience does however give us a systems perspective on problems, which we think has relevance to the situation with COVID-19.

The disturbance of COVID-19

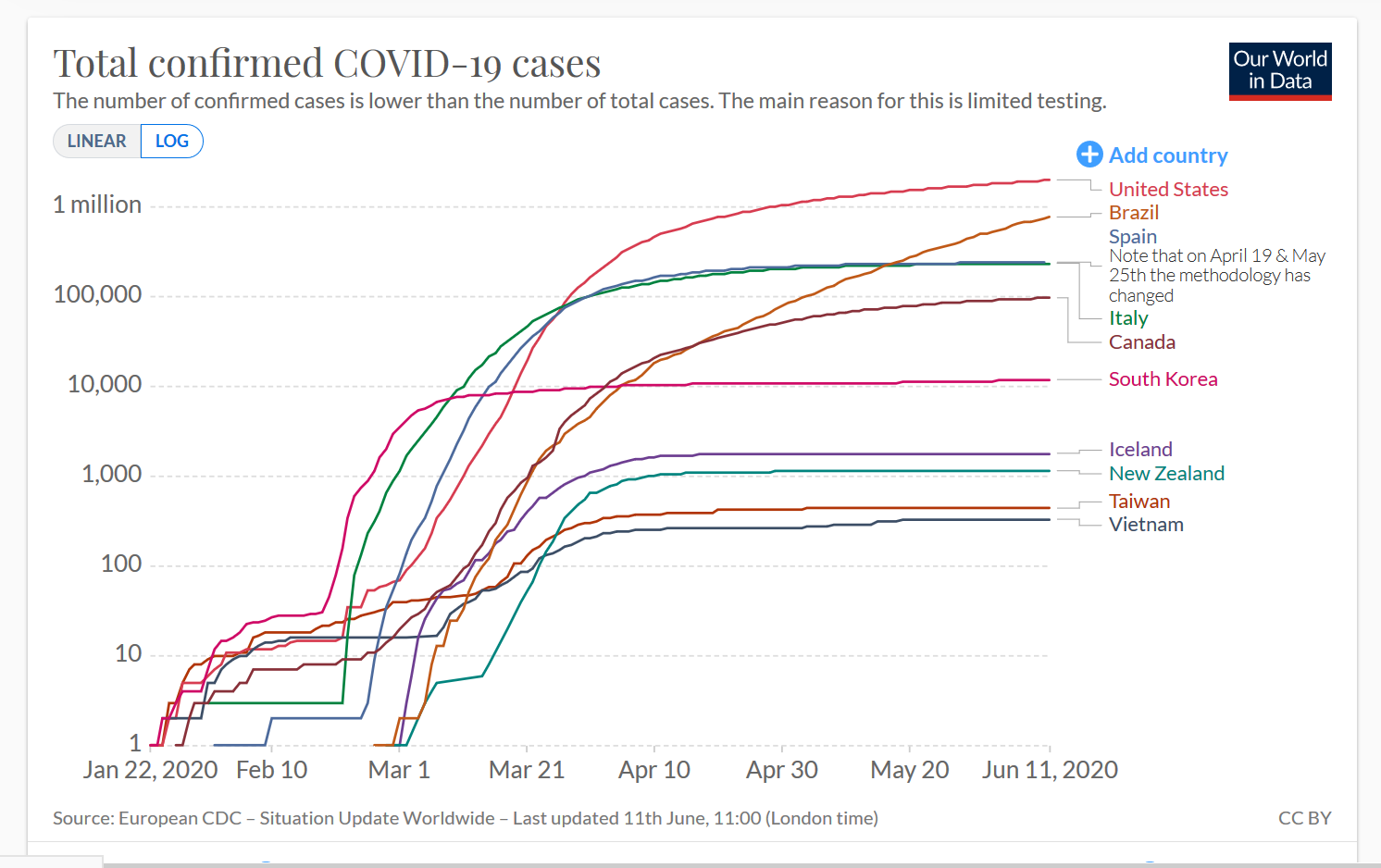

COVID-19 has led to tremendous upheaval in our health, social and economic systems, and caused more than 430,000 deaths worldwide (as of June 11, 2020). COVID-19 has been like a global X-ray machine, revealing the strengths and weaknesses of each country’s leadership, governance structures, health care, social and economic safety nets, inequities, and citizenry. The pandemic is projected to seriously exacerbate existing problems of poverty and food insecurity (UN Security Council 2020, FSIN 2020, Sumner et al. 2020). There has been enormous variability in the impacts of COVID-19 across countries, states, provinces, communities, ages, ethnicity, income classes, occupations and individuals. What can we learn from this variability about human resilience to pandemics? Countries such as Vietnam, New Zealand, South Korea, Taiwan and Iceland [Group A] flattened the case curve effectively through a mixture of early and effective actions, while other countries (e.g., Italy, Spain, USA, Brazil – Group B) failed to implement sufficient steps soon enough, with devastating consequences (see graph below, noting the log scale). Canada is between these Groups A and B, with substantial interprovincial variation (e.g., British Columbia has been much more successful than Quebec and Ontario in flattening the curve).

Thomas Pueyo (2020a; Chart 13b) elegantly summarized the contrast between countries which quickly flattened the curve and those which did not, highlighting the differences in Non-Pharmaceutical Interventions (NPIs) between the two groups. Centralized coordination, travel bans, intensive testing, contact tracing, and strong case isolation are key attributes of Group A, which were not present early enough or strongly enough in Group B. Early action was particularly critical to the success of Group A. Evidence from American cities after the 1918 wave of influenza found that those municipalities which put in place NPIs more quickly and more intensively had both fewer deaths (Hatchett et al. 2007), as well as faster and stronger economic recovery once the pandemic had subsided (Correia et al. 2020). Pueyo (2020a) did not include Vietnam, which to date has had zero deaths, due to massive testing, contact tracing and quarantine efforts; a star member of Group A despite being a developing country.

A recently published empirical study supports the benefit of NPIs for reducing the rate of growth of COVID cases. Juni et al. (2020) found that during March 2020, the growth rates of COVID-19 cases in 144 geopolitical areas were strongly negatively correlated with public health interventions, weakly negatively correlated with humidity and not correlated with latitude or temperature. Though testing procedures varied across jurisdictions, the authors calculated case growth rates within each country, which removes the effect of varying approaches to testing.

Same storm, different boats.

We see differential effects of the pandemic at multiple scales, from nations to individuals; these effects are magnified by existing disparities in income, health, employment, housing and health care. What are the underlying factors that have caused variability in the human responses to COVID-19? To what extent is this variability driven by past conditions in each jurisdiction versus the recent responses of governments, health workers and citizens to the crisis? Can the literature on resilience provide some insights on what caused these differences, and what we need to do to increase our resilience at multiple scales? How does resilience propagate across different scales? As jurisdictions attempt to move forward with policies to re-open their economies, can the practice of Adaptive Management provide some guidance on how to best evaluate and adjust these policies, and how not to do so [see post on COVID and Adaptive Management]? Exploring these questions may be helpful not only for COVID-19, but also to accelerate efforts at climate change mitigation and adaptation.

What makes some jurisdictions more resilient than others in responding to COVID?

Building on the above definitions of resilience, we consider jurisdictions which flattened or crushed the curve of COVID-19 cases during the first wave as relatively more resilient. What attributes did they have that led them to better absorb the disturbance of COVID-19, to more flexibly adapt, and to reorganize in a way that retained the function, structure and identity of their health, social and economic systems? Here are some hypotheses on the foundations of resiliency to COVID-19, synthesized from reading a wide variety of recent publications, communicating with scientists involved in modelling COVID-19, and conversing with colleagues:

Capable leaders that adapt quickly to a fast-changing situation. During a pandemic, capable leaders consult extensively with health experts and colleagues across multiple domains, make difficult decisions quickly with incomplete information, communicate clearly and compassionately to the public what is known and unknown, and kindly encourage each citizen to do their part.

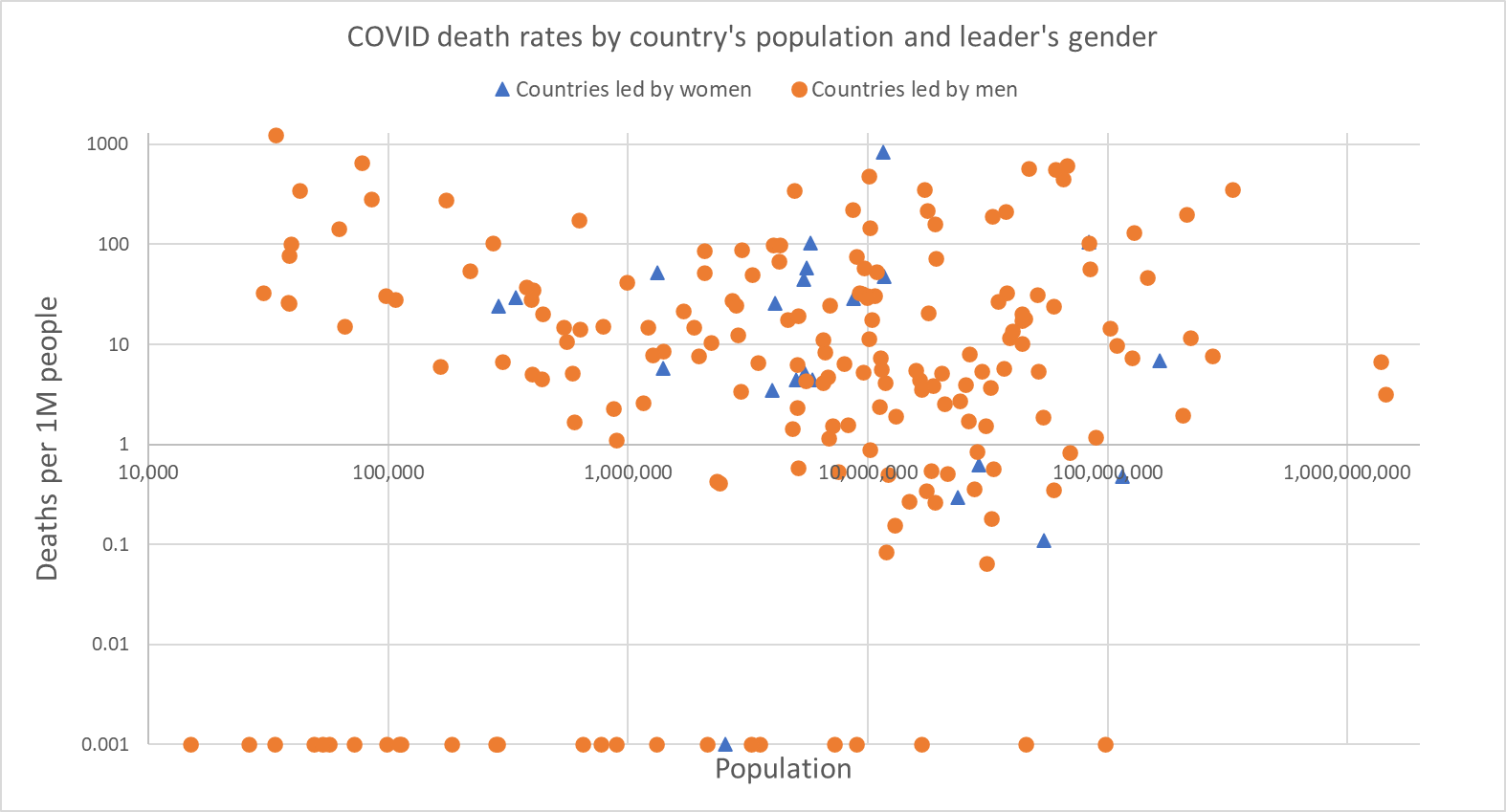

Many of the countries that have flattened the curve well (Denmark, Finland, Germany, Iceland, Norway, New Zealand, Singapore, Taiwan) are led by women. How general is this pattern across the globe? Does the size of a country’s population also affect death rates? The data on death rates versus population size are shown below for female-led countries (blue triangles) and male-led countries (orange circles). Caution is warranted in drawing general conclusions, particularly as data quality varies across countries. While most of the points at the top of the graph (death rates > 100 / 1M people) are from male-led countries, that’s also the case for the points at the bottom of the graph with zero deaths. South Korea, Vietnam and Singapore are led by men who were very successful in leading their countries through this crisis. And Belgium (with 833 deaths / million people, second highest in the world, next to San Marino at 1,238) is led by a woman. Small countries with fewer than 100,000 people (left side of the graph) appear to have a bimodal distribution of death rates – seven countries with more than 100 deaths / million people, and 12 with zero. This is likely because the occurrence of one cluster of COVID-19 cases can create a high death rate in small country. Bearing in mind these patterns, the overall numbers are intriguing: across the 21 countries led by women (with a total population of 549 million) there have been 40 COVID deaths per million people (i.e., [total deaths in all female-led countries] / [total population in millions in all female-led countries]). The comparable figure for the 193 countries led by men (with a total population of 7.2 billion) is 57. Clearly, much more analysis is required on the attributes of capable leaders, and the many other variables affecting death rates (e.g., health care systems, income distributions, rates of poverty and unemployment).

Sources: Data on which countries are led by women: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women_in_government

Data on COVID-19 deaths (up to June 11, 2020) and population sizes: https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/

It may be that some women leaders have more of the characteristics required in a pandemic, as suggested in several recent articles (Taub 2020, Elesser 2020, Kristof 2020). It’s also possible that countries which elect female leaders have other characteristics (e.g., inclusive political institutions at multiple levels, well-educated citizens) which are valuable during a pandemic, as discussed by Lewis (2020). Resilience is multi-layered and multi-faceted, as we explain below. We’re still only in the first phase of the pandemic, far too early to assess the attributes of long term resilience by a suite of well-monitored social and economic indicators (see post on COVID and Adaptive Management).

Agile governments at multiple levels. Government officials across multiple departments and levels (national, state/provincial, municipal) are well briefed and well-coordinated, trust advice from health scientists, and implement actions promptly. Strong central governments which accept their responsibility for leadership and coordination, supported by well-trained and well-funded staff with the necessary skills, are much more likely to have the adaptive capacity to quickly respond to a sudden health crisis. Publicly funded health care allows for more rapid coordination of actions and information exchange, without the barriers created by private hospitals and health management organizations. Vietnam has a well-coordinated system of 63 provincial CDCs (centres for disease control), 700 district-level CDCs, and 11,000 commune health centres (Gan 2020). Innovations such as remote medical consultations, paramedics doing house calls, hotlines for consultations on symptoms, are all more easily implemented through a public health care system. Speed and coordinated action across many scales is critical. Modeling studies for the period from March 15th to May 3rd, 2020 suggest that if social distancing had been implemented just a week earlier in the United States, it could have saved about 35,000 lives; doing so two weeks earlier would have saved 58,000 lives (Pei et al. 2020). Pei et al. also quantify similar risks from the premature relaxation of NPIs.

The lead spokesperson is a scientist who builds trust with the public. Duhigg (2020) describes some of the protocols developed by the U.S. Epidemic Intelligence Service (E.I.S.) to guide epidemiologists in building trust with the public during an epidemic. Duhigg quotes John Cowden (a Scottish epidemiologist): “Being approximately right most of the time is better than being precisely right occasionally” and Richard Besser (an EIS alumnus): “If you have a politician on the stage, there’s a very real risk that half the nation is going to do the opposite of what they say.” Epidemiologists must maintain their persuasiveness even as their advice shifts with new data, experiments and insights. In British Columbia, daily briefings by the provincial health officer Dr. Bonnie Henry showed a deep level of empathy for people who had lost family members and friends to COVID-19, clearly explained complex data and modelling, and established a high level of trust, calm and kindness among the public (Porter 2020). Work cited in Denworth (2020) indicates that citizens who are high in empathy are more likely to engage in appropriate health behaviours such as social distancing. Spokespersons who model empathy therefore build community resilience.

Responsive and resilient citizens. COVID has led to about one third of the world’s population being in lockdown, “arguably the largest psychological experiment ever conducted” (Elke van Hoof, cited in Denworth 2020). The resilience of a country depends on the resilience of its citizens. At a societal scale, strong educational programs in science and critical thinking, together with the trust in government and their spokespersons discussed above, may be critical to promoting rational behaviour and compliance with NPIs during a crisis. While rapid dissemination of information is essential for informing public health professionals and citizens of a rapidly changing situation and appropriate behaviours, misinformation spread virally across social media platforms can also undermine the need for rational responses and community resiliency (Limaye et al., 2020; Van Bavel et al. 2020).

The resilience of ecosystems to perturbations varies with its history of management of past stresses, and the effects of that history on its current structure (Holling 1973). This is also the case for countries. In Peru, where the large informal economy requires many citizens to leave home each day to find income and food, and there is a chronically underfunded healthcare system, very prompt actions by the government (lockdowns, widespread testing) have been insufficient to flatten the curve of COVID-19 cases (Collins 2020). In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, historical conflict led to a long-term decline in the level of trust in government institutions and information by many urban citizens, which in turn undermined their responses to Ebola during 2018-19, including denial of the existence of the disease and low compliance with preventive behaviours (Vinck et al. 2019). Prompt and appropriate actions in response to a current crisis may therefore be insufficient to overcome a long history of structural problems that reduce societal resiliency. The devastating effects of hurricane Katrina on New Orleans provide a parallel example from the climate change domain. The same structural factors which reduced resilience to hurricane Katrina likely have contributed to Louisiana being particularly hard hit by COVID-19 (death rate / 1M people of 660 as of June 18, the seventh highest of the 50 states in the U.S.; https://www.worldometers.info/coronavirus/country/us/).

At an individual level, Denworth (2020) notes that personal resilience is correlated with optimism, the ability to keep perspective, strong social support, and flexible thinking. It’s strengthened by getting enough sleep, observing a routine, exercising, eating well, and maintaining strong social connections. Denworth cites research from past epidemics and other crises (hurricanes, terrorist attacks) indicating that two thirds of people maintain relatively stable psychological and physical health, one quarter struggle with temporary psychopathology such as depression or PTSD, and one tenth suffer lasting distress. Studies in the UK since mid-March indicate that those living alone and younger people were suffering the highest levels of anxiety, but that there was a slight decrease in anxiety levels once the lockdown was declared (Denworth 2020).

Past perturbations can increase adaptive capacity. Past epidemics have led to hard lessons which sharpened the adaptive capacity of some countries to respond, building the talent and capability to rapidly think through the crisis, do testing and contact tracing, and supply needed medical equipment. South Korea experienced SARS IN 2002, H1N1 in 2009 and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2015 (Thompson 2020). After MERS, South Korea developed a system to rapidly expand its testing capabilities (Wikipedia). When the genetic sequence of COVID-19 was identified, the government identified twenty reputable vendors and had kits available within a matter of weeks (Mukherjee 2020). Taiwan had similar scars from past epidemics, which led to strong actions to increase their adaptive capacity prior to COVID-19 (Kornreich and Jin 2020). Vietnam was the first country to be hit by SARS in 2003, and quickly implemented intensive contact tracing (Nakashima 2003), which has been critical to its success with COVID-19. In contrast to South Korea, Vietnam and Taiwan, bureaucratic delays and faulty testing kits led to months of delays in reliable testing in the U.S. (Mukherjee 2020); Pueyo (2020b) thoroughly examines what’s required for testing and contact tracing. Dr. Henry, British Columbia’s health officer, had critical experience with Ebola in Uganda and SARS in Toronto, past perturbations which increased her preparedness for COVID.

Redundancy in critical supply chains. Personal protective equipment and other medical equipment such as ventilators were critical during the pandemic, yet many countries tragically did not have adequate supply chains when COVID-19 hit (unlike South Korea, described above). Mukherjee (2020) attributes this failure in the U.S. partly to market-driven, efficiency-obsessed culture of hospital administrators: “The numbers in the bean counter’s ledger are now body counts in a morgue…we’ve been over-taught to be overtaut”. Agility in food supply chains is critical during a pandemic, and COVID-19 has led to some creative adaptations in Canada (e.g., shifts in food supplies from restaurants to grocery stores, local distilleries supplying hand sanitizer, local butchers providing beef during the closure of large meat packing plants); fluctuations in food supply chains are likely to continue (Burt and Robinson 2020). Interestingly, social distancing has made citizens tremendously reliant on the Internet, which has huge redundancy in its network of information supply chains. The Internet has functioned very reliably during global lockdowns as virtual communications increased exponentially, helping to maintain social connections, but also (as discussed above) rapidly circulating misinformation. The resilient Internet can therefore both support personal resilience and undermine it.

Creative, rapid action using available resources. Iceland made use of deCODE, a large genetics testing company studying the connection between disease and genetic variation, to test people who had no symptoms or only very mild ones, picking up many cases that otherwise would have been missed (Kolbert 2020), and providing valuable information for health scientists around the world on the incidence of COVID-19 in asymptomatic people (John 2020). Iceland has had the highest rate of testing in the world, up to 15.5% of its population by May 17th of this year (Kolbert 2020).

Paying attention and learning quickly from others. The science fiction writer William Gibson has said: “The future is already here. It’s just not very evenly distributed.” (cited in Rothman 2020). There was time to learn from China and other countries that were hit early by COVID-19; China’s present was other countries’ future. The Group A countries paid close attention and acted quickly, while many of the Group B countries delayed. Rapid learning and access to large data sets is also essential for doctors to explore hypotheses and develop treatments for a novel virus. Mukherjee (2020) describes how the electronic medical-record systems in the U.S., optimized for private billing, are a huge obstacle to data synthesis across multiple hospitals and patient histories. Mukherjee comments: “a storm-forecasting system that warns us after the storm has passed is useless.”

Parting Thoughts

Each perturbation to a system is unique, requiring different forms of adaptation to ensure that social-economic-ecological systems remain resilient, or at least can rebuild resilience after being damaged. Preparation for fires, hurricanes and floods requires different actions than preparation for a pandemic. But many of the underlying factors discussed above which increased resilience to COVID-19 in some jurisdictions (i.e., capable leadership, agile governance coordinated across multiple scales, prominence of scientists in communication, informed and educated citizens, innovation and creativity, attentiveness and fast response, redundancy in supply chains, learning from others and from past experience) can increase the resilience of our societies to many other global challenges, including climate change, poverty alleviation, ocean acidification, habitat loss and species extinctions. I am hopeful that the examples of success with COVID-19 can provide some guidance to how we tackle a larger suite of problems.

Why is it that some leaders have the verve,

To ask, listen, act, and flatten the curve?

Is it them, or the citizens they serve?

Trust, history, science, a kindly love?

Surely it must be, all of the above.

References

Burt, M. and M. Robinson. 2020. What we grow and eat in Canada will change due to COVID-19. The Conference Board of Canada. June 8, 2020. https://www.conferenceboard.ca/insights/blogs/what-we-grow-and-eat-in-canada-will-change-due-to-covid-19

Collins, D. Peru’s coronavirus response was ‘right on time’ – so why isn’t it working? The Guardian. May 20, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2020/may/20/peru-coronavirus-lockdown-new-cases?CMP=share_btn_link

Correia, S., Luck, S. and Verner, E. 2020. Pandemics Depress the Economy, Public Health Interventions Do Not: Evidence from the 1918 Flu (June 5, 2020). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3561560 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3561560

Denworth, L. 2020. The biggest psychological experiment in history is running now. Scientific American

Elesser, K., 2020. Are Female Leaders Statistically Better At Handling The Coronavirus Crisis? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/kimelsesser/2020/04/29/are-female-leaders-statistically-better-at-handling-the-coronavirus-crisis/#28d98a27539c

Food Security Information Network (FSIN). 2020. 2020 Global Report on Food Crises: Joint Analysis for Better Decisions. 240 pp. https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000114546/download/?_ga=2.73706002.1046114401.1592391562-1602396827.1592391562

Gan, N. 2020. Vietnam : How this country of 95 million kept its coronavirus death toll at zero. May 30, 2020. https://www.msn.com/en-us/news/world/vietnam-how-this-country-of-95-million-kept-its-coronavirus-death-toll-at-zero/ar-BB14MxiR

Gunderson, L.H. and C.S. Holling 2002. Panarchy. Understanding transformations in human and natural systems. Island Press. 507 pp.

Hatchett, R.J., C.E. Mecher and M. Lipsitch. 2007. Public health interventions and epidemic intensity during the 1918 influenza pandemic. PNAS 104(18): 7582-7587. www.pnas.org_cgi_doi_10.1073_pnas.0610941104

Holling, C.S. (1973). “Resilience and stability of ecological systems” (PDF). Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics. 4: 1–23. doi:10.1146/annurev.es.04.110173.000245.

Holling and Gunderson. Resilience and Adaptive Cycles. Chapter 2 in Gunderson and Holling 2002, Panarchy. Island Press. 507 pp.

Kolbert, E. 2020. How Iceland beat the coronavirus. The New Yorker. June 1, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/06/08/how-iceland-beat-the-coronavirus

Kornreich, Y. and Y. Jin. 2020. The Secret to Taiwan’s Successful COVID Response. Asia Pacific Foundation. https://www.asiapacific.ca/publication/secret-taiwans-successful-covid-response

Kristof, N. 2020. What the pandemic reveals about the male ego. New York Times. June 13, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/13/opinion/sunday/women-leaders-coronavirus.html

John, T. 2020. Iceland lab’s testing suggests 50% of coronavirus cases have no symptoms. CNN. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/01/europe/iceland-testing-coronavirus-intl/index.html

Jüni, P., M. Rothenbühler, P. Bobos, , K.E. Thorpe, B.R. da Costa, D. N. Fisman. A.S. Slutsky, D. Gesink. 2020. Impact of climate and public health interventions on the COVID-19 pandemic: a prospective cohort study. CMAJ 2020. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.200920; early-released May 8, 2020.

Lewis, H. 2020. The pandemic has revealed the weakness of strongmen. The Atlantic. May 6, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2020/05/new-zealand-germany-women-leadership-strongmen-coronavirus/611161/?utm_source=atl&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=share).

Limaye, R.J., M. Sauer, J. Ali, J. Bernstein, B. Wahl, A. Barnhill, and A. Labrique. 2020. Building trust while influencing online COVID-19 content in the social media world. The Lancet. April 21, 2020. https://www.thelancet.com/journals/landig/article/PIIS2589-7500(20)30084-4/fulltext

Mukherjee, S. 2020. What the coronavirus crisis reveals about American medicine. The New Yorker, May 4, 2020. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2020/05/04/what-the-coronavirus-crisis-reveals-about-american-medicine

Pei, S., S. Kandula, J. Shaman. 2020. Differential effects of intervention timing on COVID-19 spread in the United States. Version 2. medRxiv. Preprint. 2020 May 20. doi: 10.1101/2020.05.15.20103655

Porter, C. 2020. The top doctor who aced the coronavirus test. The New York Times. June 5, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/05/world/canada/bonnie-henry-british-columbia-coronavirus.html

Pueyo, T. 2020a. Coronavirus: The Hammer and the Dance. What the Next 18 Months Can Look Like, if Leaders Buy Us Time. Medium – March 19, 2020. https://medium.com/@tomaspueyo/coronavirus-the-hammer-and-the-dance-be9337092b56

Pueyo, T. 2020b. Coronavirus : how to do testing and contact tracing. Medium – April 28, 2020. https://medium.com/@tomaspueyo/coronavirus-how-to-do-testing-and-contact-tracing-bde85b64072e

Rothman, J. Mirror World: How William Gibson makes his science fiction real. The New Yorker. December 16, 2019. https://www.newyorker.com/magazine/2019/12/16/how-william-gibson-keeps-his-science-fiction-real

Sumner, A., Eduardo Ortiz-Juarez, C. Hoy. Precarity and the pandemic. WIDER Working Paper 2020/77. 26 pp. https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/Publications/Working-paper/PDF/wp2020-77.pdf

Thompson, D. What’s behind South Korea’s COVID-19 exceptionalism? The Atlantic. May 6, 2020. https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2020/05/whats-south-koreas-secret/611215/

Taub, A. Why are women-led nations doing better with Covid-19? New York Times – May 15, 2020. https://www.nytimes.com/2020/05/15/world/coronavirus-women-leaders.html

United Nations Security Council 2020. Senior Officials Sound Alarm over Food Insecurity, Warning of Potentially ‘Biblical’ Famine, in Briefings to Security Council. https://www.un.org/press/en/2020/sc14164.doc.htm

Van Bavel, J.J. et al. 2020. Using social and behavioural science to support COVID-19 pandemic response. Nature Human Behaviour 4 : 460-471. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-020-0884-z

Vinck, P., P.N. Pham, K.K. Bindu, J. Bedford, E.J. Nilles. 2019. Institutional trust and misinformation in the response to the 2018–19 Ebola outbreak in North Kivu, DR Congo: a population-based survey. Lancet Infect Dis 2019; 19: 529–36. Published Online March 27, 2019. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(19)30063-5

Walker, B.; Holling, C. S., Carpenter, S. R. and Kinzig, A. (2004). “Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems”. Ecology and Society. 9 (2): 5. https://doi.org/10.5751%2FES-00650-090205

Yorque, R., B. Walker, C.S. Holling, L.H. Gunderson, C. Folke, S.R. Carpenter and W.A. Brock. 2002. Toward an Integrative Synthesis. Chapter 16 in Gunderson and Holling 2002, Panarchy. Island Press. 507 pp.