Trinity River Restoration Plan

Building inter-agency consensus for the scientific foundation of a multi-million dollar restoration project on the Trinity River in Northwestern California.

Location: |

Trinity River basin, California, USA; 40.803836, -123.392703 | |

Client: |

Trinity River Restoration Program | |

Duration: |

2009 – 2010 | |

Team Member(s): |

Dave Marmorek, Darcy Pickard, Marc Porter, Clint Alexander, and former staff Katherine Wieckowski | |

Practice Area(s): |

Adaptive Management, Fisheries & Aquatic Sciences | |

Services Employed: |

Facilitation & Stakeholder Engagement, Ecological Modelling, Statistical Design & Analysis |

The Trinity River Restoration Program (TRRP) is a large-scale, adaptive management program targeting the restoration the Trinity River and its populations of salmon, steelhead, and other fish and wildlife.

Our firm has a decade-long relationship supporting the TRRP in its mandate, starting in 2004 with the development of a rigorous adaptive management approach to monitor and improve the effectiveness of the TRRP’s restoration work. We developed TRRP’s Integrated Assessment Plan (IAP), a foundational science document for the restoration. Developing the IAP was a multi-year effort that involved the participation of over 25 scientists.

As an adaptive management project, the TRRP has to be very clear and efficient in monitoring its own restoration work to keep track of whether their efforts are helping, doing nothing or even worse, doing harm. “As we do different things, whether it’s mechanical restoration on the river or augmenting gravel, we don’t know beforehand with certainty what the outcome is going to be and so we need to be watching how the river and the fish and habitat is responding to see if what we’re doing is effective or even if it’s the right thing to do,” says David Gaeuman, a geomorphologist with the Bureau of Reclamation. “If a [restoration] project doesn’t perform the way we want it to, we want to adjust our actions. We don’t want to keep making the same mistakes. We need to be paying attention to what the response is to our actions.”

The feedback mechanism in place to measure the impact of TRRP’s restoration actions involved detailed and complex monitoring and assessment programs that each fed into testable scientific hypotheses, which in turn were tied to one of six consensus objectives agreed to by stakeholders. The IAP was the master plan that mapped out these mechanisms for project staff. It took several years and countless stakeholder meetings to complete and has stood the test of time. In the words of Gaeuman, “it’s the encyclopedia about everything you might want to find out about [TRRP’s] monitoring programs.”

While our team’s scientific expertise has been critical in supporting the TRRP’s adaptive management approach to river restoration, just as integral to the project’s success was ESSA’s value in bringing disagreeing stakeholders to the table to find common ground and objectives.

The Trinity River: Mined, dammed, diverted and now in restoration.

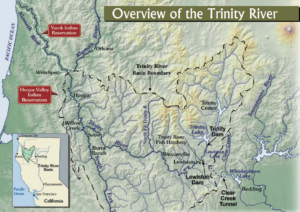

The Trinity River is the main tributary to the Klamath River, which enters the Pacific Ocean in Northern California. The Trinity once supported large populations of fall- and spring-run Chinook salmon, as well as smaller runs of coho salmon and steelhead. For millennia, the fish, plants and animals along the river supported the Hoopa and Yurok tribes and their culture.

Map overview of the Trinity River showing location and key features, reproduced from the US Bureau of Reclamation Record of Decision brochure (USBR 2000).

It wasn’t until the late 1840s that disturbance to the river began with the discovery of gold. Industrial logging began in the watershed in the 1950s. Despite these stressors in the watershed, the salmon and steelhead continued to return to the river in healthy numbers. In 1958 a plan was made to increase water into California’s Central Valley in part by moving water from the Trinity into the Sacramento River with the help of two dams on the river.

The construction of the Lewiston and Trinity dams on the Trinity River in 1964 diverted the majority of the river’s water for the generation of hydroelectric power, and water for farming, industry and human consumption. Lower flows stifled the natural river processes that create fish habitat. By 1970, the extent of alteration to the river, and the decline in salmon and steelhead was obvious. For instance, the Trinity River Dam is estimated to have caused declines of 80% in the fall-run Chinook salmon, with similar declines seen in the Spring-run Chinook salmon, coho salmon and steelhead trout.

Concerns about the decline in the river’s overall health, and precipitous drops in fish numbers resulted in a government Record of Decision in the year 2000 to create the Trinity River Restoration Program that would implement the restoration of the Trinity River and its fish and wildlife populations.

The TRRP spends roughly $10 million per year and is a collaboration between the following: US Fish and Wildlife Service, US Bureau of Reclamation, Hoopa Valley Tribe, Yurok Tribe, California Department of Fish and Game, US Forest Service, California Trout, and California Department of Water Resources.

The restoration effort is fortunate in that it has generous funding, the lion’s share of which comes from the Department of Interior through the Bureau of Reclamation. It also has a lot of water allocated to the restoration, about half of the water in the system, mostly thanks to the tribes.

The Trinity restoration distinguishes itself by its philosophy of setting the river up to fix itself so it can function as a healthy system in perpetuity. “A lot of our restoration involves setting up the river so it can start functioning like a natural river and create its own habitat,” says Gaeuman.

Multiple stakeholders, little inter-agency trust, and lots of science to do.

In addition to the logistical challenge of outlining an adaptive management plan for the restoration of 40 miles of river, the TRRP also faced the more nuanced — and at times intractable — problem of the diversity of its stakeholders. It was this more “human” problem that had to be resolved before any meaningful headway could be made as far as science work on the ground.

“The problem was a really diverse partnership with a bunch of agencies and governments and tribes that that have their own interests and we were trying to figure out how you get around that,” recalls Gaeuman, who reserved particular praise for ESSA’s Darcy Pickard for her ability to bridge these divides by finding common ground to move things forward.

“It was a really contentious political environment and ESSA waded in there and they took it on. We would have gotten nowhere at all without them.”

Pickard, for her part, is trained in statistics, a field where finding commonalities is just as important as spotting differences. It’s a trait that she found incredibly useful on this project, especially when it came to those early and most contentious workshops. “As in all these projects, there are complexities from the science point of view but also from the value judgements point of view. For this project there were people in the room coming at the problem from different sides with different priorities,” says Pickard. “It was hard to agree on what were the most important scientific questions to ask and try to answer. As independent scientists, we helped them work through a process of developing hypotheses that were testable to answer those questions.”

Refereeing and consensus building to create a clear and robust monitoring program

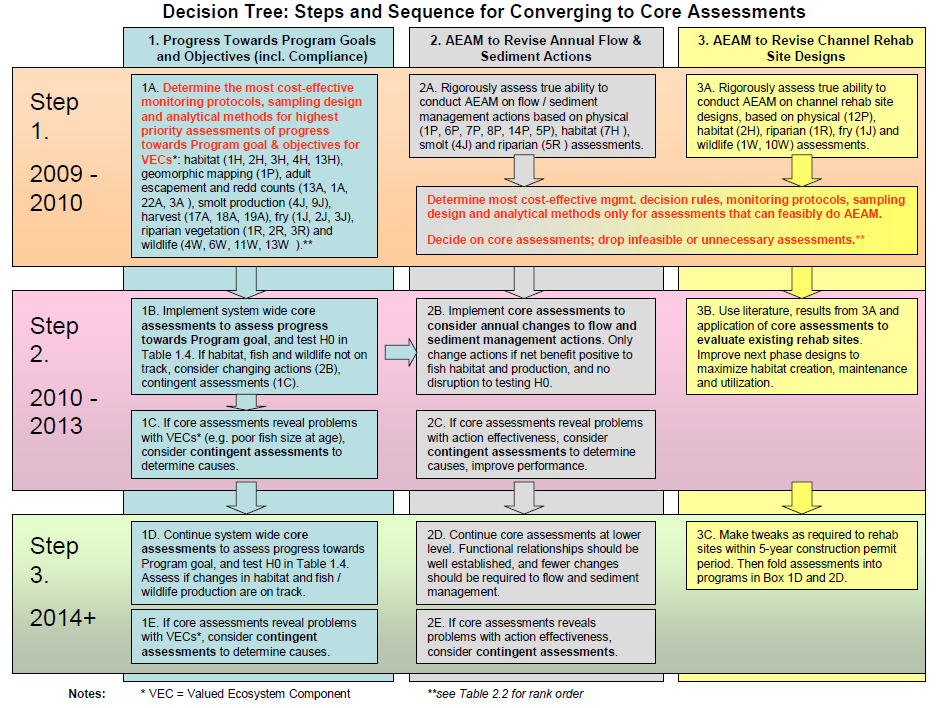

In order to have an effective adaptive management plan, the TRRP stakeholders needed to reach agreement on what they wanted to monitor and develop testable hypotheses accordingly. As part of putting together the IAP, ESSA used a collaborative workshop-based approach to help to identify six major restoration objectives for the TRRP. These provided the organizing framework for the IAP, and for the restoration and monitoring activities in the Trinity River. The six objectives were then teased out into testable hypotheses and subhypotheses, ultimately yielding 75 unique assessments.

Adaptive management is only meaningful when there is a management lever to manipulate. In this instance there were three primary management actions: managing the flow of the river, managing the fine and coarse sediment, and rehabilitating the river channel. Scientists monitor the effects of each action.

Irrigated riparian planting along the Trinity River banks, one key type of restoration pursued as part of the Trinity River Restoration Program.

Creation of new habitat complexity around an island through the installation of logs and other instream structures, another key type of restoration pursued as part of the Trinity River Restoration Program.

Monitoring of western pond turtles, a key species that will benefit from the Trinity River Restoration Program. Regular monitoring of valued ecosystem components is critical to understanding the effectiveness of restoration actions and adjusting, if necessary, through adaptive management.

“The IAP is the best thing we have for laying out what we monitor, and why we monitor it,” says Gaeuman. “We’re just building so many things so quickly and nobody can really keep track of them. Darcy was really helpful in trying to look at how we can really assess if our restoration sites are performing as we intended them to perform.”

Example of a decision tree from the TRRP IAP that helped restoration managers to decide when to move to new phases of restoration.

We further supported the implementation of the adaptive management framework described in the IAP, including: implementing a rigorous and integrated sampling design, building an online data portal, completing data analyses to evaluate IAP hypotheses, and improving the methods used to estimate out migrating salmon smolts.

“Your vision of how to implement the science part of this program has been remarkable. We have all come a long way in the last two years.”

– Nina Hemphill, Fish Biologist, Trinity River Restoration Program in regards to ESSA’s role in facilitating development of a science framework for the Trinity River Restoration Program.

“The IAP team (and ESSA personnel) invested many long and thoughtful hours of discussion, writing, and editing to reach this important milestone. I think everyone directly involved in the process can feel a great deal of personal and professional satisfaction, and all other program partners should be greatly appreciative of a job well done.”

– Doug Schleusner, Executive Director, Trinity River Restoration Program, on the completion of the Integrated Assessment Plan led by ESSA.

- Trinity River Restoration Program Website

- ESSA Technologies. 2004. Trinity River Restoration Program integrated information management system user needs assessment, v 2.0.

Download Document - Marmorek, D. R. 2010. Adaptive environmental assessment and management in the TRRP: progress, challenges and opportunities. Oral presentation provided at the Trinity River Restoration Program’s 2010 Trinity River Science Symposium. ESSA Technologies, Vancouver, British Columbia.

Download Document.