Our world is noisy, complex, and interconnected. Conventional approaches to managing social-ecological systems often fall short in resolving today’s contentious high stakes problems. Noise, complexity, and interdependencies can make it harder to know what to do or, just as frequently, organizations are unable to discern whether policies and actions are working as intended. We believe that rigorous science, collaboration, innovation and creativity improve how people manage environmental and social challenges in a way that benefits ecosystems, human communities and ultimately our clients.

Our corporate mission is to “bring together people, science and analytical tools to sustain healthy ecosystems and human communities”.

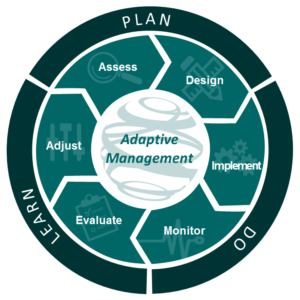

We achieve this mission by helping clients deal with tough emerging problems by applying a neutral, thorough evaluation of evidence, and by exploring innovative solutions for a more sustainable world. The key to our success is a unique and rich combination of systems thinking, inclusive facilitation and a focus on learning. Our approach is grounded in Adaptive Environmental Assessment and Management (AEAM) or Adaptive Management (AM), which provide a fundamentally different way of framing problems by looking at them with a unique mindset.

- embrace uncertainties and focus on those that have the most influence on decision making;

- use ‘systems thinking’ as a way to analyze complex social-ecological systems;

- adopt scientifically rigorous approaches for developing and testing hypotheses;

- encourage collaborative participatory processes to bring together diverse perspectives.

Where the conditions are right, AM can be applied in a holistic and structured way, which proceeds through distinct stages of an ongoing learning loop with clear and purposeful planning, doing and learning. Often, the AM mindset itself catalyzes a systematic and collaborative approach to how we work with clients and stakeholders to craft solutions that are tailored to each specific context. AM requires synthesizing diverse areas of expertise (e.g., natural sciences, ecological modelling, climate change adaptation and environmental assessment), all of which are primary practice areas that ESSA provides, both in North America and internationally. We’ve recently made some major advances in melding AM with climate change adaptation, described here.

Although the concepts of AM have been around for decades, they are now becoming increasingly popular for confronting uncertainties in many different environmental contexts: environmental assessment, climate change adaptation, natural resource management, conservation, ecosystem restoration, and international development. Yet there are common misunderstandings or differences in the way it is applied. A common view is that AM simply means being flexible so you can “adapt as you go”, as opposed to using a more systematic approach to learning over time. Over ESSA’s nearly 40 years of applying AM we have developed a sharp appreciation for the difference between “real” and “pretend” AM.

When applied well in the right circumstances, an AM mindset delivers a variety of benefits: it can help empower organizations and communities to take action, guide investments in monitoring, clarify the purpose and needs for reporting, and improve our understanding about the effects of different actions. Ultimately, these benefits translate into greater certainty for decision-makers and stakeholders in the long run, leading to better decisions with fewer regrets.

Benefits of the Adaptive Management Process

Although our mindset is rooted in Adaptive Management, our approach involves more than just rigorous AM. We stand on the shoulders of giants; those who broke trail and contributed to a better understanding of social-ecological systems. Explore this curated reading list of papers and books to learn more about what grounds us and the way we do our work.

- Bohensky, E. L., and Y. Maru. 2011. Indigenous knowledge, science, and resilience: what have we learned from a decade of international literature on “integration”? Ecology and Society 16(4): 6. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-04342-160406

- Dietz, T., E. Ostrom and P.C. Stern. 2003. The Struggle to Govern the Commons. Science. 302 (5652): 1907-1912. DOI:1126/science.1091015

- Duinker, P.N., and L.A. Greig. 2006. The impotence of cumulative effects assessment in Canada: ailments and ideas for redeployment. Environmental Management. 37(2): 153-61. DOI:1007/s00267-004-0240-5

- Dunlap, J.C., and P.R. Lowenthal. 2016. Getting graphic about infographics: Design lessons learned from popular infographics. Journal of Visual Literacy. 35: 42-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/1051144X.2016.1205832

- Folke, C., T. Hahn, P. Olsson, and J. Norberg. 2005. Adaptive governance of social-ecological systems. Annu. Rev. Environ. Resour. 30: 441–473. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.energy.30.050504.144511

- Grant, W.E. 1998. Ecology and natural resource management: reflections from a systems perspective. Ecological Modelling. 108: 67-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-3800(98)00019-2

- Greig, L.A., D.R. Marmorek, C. Murray, and D.C.E. Robinson. 2013. Insight into enabling adaptive management. Ecology and Society 18(3): 24. http://dx.doi.org/10.5751/ES-05686-180324

- Holling, C. S., and A.D. Chambers. 1973. The Nurture of an Infant. BioScience. 23 (1): 13-20. https://doi.org/10.2307/1296362

- Holling, C.S. and G.K. Meffe. 1996. Command and control and the pathology of natural resource management. Conservation Biology. 10(2): 328-337. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-1739.1996.10020328.x

- Houde, N. 2007. The six faces of traditional ecological knowledge: Challenges and opportunities for Canadian co-management arrangements. Ecology and Society 12(2): 34. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol12/iss2/art34/

- Jones, M.L., R.G. Randall, D. Hayes, W. Dunlop, J. Imhof, G. Lacroix, and N.J.R. Ward. 1996. Assessing the ecological effects of habitat change: moving beyond productive capacity. Canadian Journal of Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences 53 (Suppl. 1): 446–457. https://doi.org/10.1139/f96-013

- Lackey, R.T. 2007. Science, Scientists, and Policy Advocacy. Conservation Biology 21 (1): 12-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1523-1739.2006.00639.x

- Link, J.S., T.F. Ihde, C.J. Harvey, S.K. Gaichas, J.C. Field, J.K.T. Brodziak, H.M. Townsend, and R.M. Peterman. 2012. Dealing with uncertainty in ecosystem models: The paradox of use for living marine resource management. Progress in Oceanography 102: 102-114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pocean.2012.03.008

- Martin, T.G., M.A. Burgman, F. Fidler, P.M. Kuhnert, S. Low-Choy, M. McBride, and K. Mengersen. 2011. Eliciting expert knowledge in conservation science. Conservation Biology 26 (1): 29-38. DOI:1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01806.x

- Nichols, J.D., and B.K. Williams. 2006. Monitoring for conservation. TRENDS in Ecology and Evolution 21 (12): 668-673. DOI:1016/j.tree.2006.08.007

- Reed, M.S. 2008. Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biological Conservation. 141: 2417-2431. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014

- Segrera, S., R. Ponce-Hernández, and J. Arcia. 2003. Evolution of Decision Support System Architectures: applications for land planning and management in Cuba. Journal of Computer Science and Technology. 3 (1): 40-46. https://pdfs.semanticscholar.org/7c27/3712e246ef13580d7367834035b4f6af23b2.pdf

- Walker, B., C.S. Holling, S.R. Carpenter, and A. Kinzig. 2004. Resilience, adaptability and transformability in social–ecological systems. Ecology and Society 9 (2): 5. http://www.ecologyandsociety.org/vol9/iss2/art5/

- Walters, C.J., and C.S. Holling. 1990. Large-scale management experiments and learning by doing. Ecology. 71 (6): 2060-2068. https://doi.org/10.2307/1938620

- Wilby, R.L., and S. Dessai. 2010. Robust adaptation to climate change. Weather. 65: 180-185. https://doi.org/10.1002/wea.543

- Gregory, R., L. Failing, M. Harstone, G. Long, T. McDaniels, and D. Ohlson. 2012. Structured Decision Making: A practical guide to environmental management choices. Wiley Blackwell. DOI:10.1002/9781444398557

-

Gunderson, L.H., and C.S. Holling. 2001. Panarchy: Understanding Transformations in Human and Natural Systems. Island Press. https://islandpress.org/books/panarchy

- Gunderson, L., C.S. Holling, and S. Light (editors). 1995. Barriers and Bridges to the Renewal of Ecosystems and Institutions. Columbia University Press. https://cup.columbia.edu/search-results?keyword=Barriers+and+Bridges+to+the+Renewal+of+Ecosystems+and+Institutions

- Hilborn, R., and M. Mangel. 1997. The ecological detective: confronting models with data. Princeton, N.J, Princeton University Press. https://press.princeton.edu/titles/5987.html

- Holling, C.S. 1978. Adaptive Environmental Assessment and Management. Chichester, NY, Wiley. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/823/1/XB-78-103.pdf

- Kaner, S. 2014. Facilitator’s guide to participatory decision making. Jossey-Bass. https://www.wiley.com/en-us/Facilitator%27s+Guide+to+Participatory+Decision+Making%2C+3rd+Edition-p-9781118404959

- Lee, K.N. 1993. Compass and gyroscope: Integrating science and politics for the environment. Island Press. https://islandpress.org/book/

compass-and-gyroscop - Morgan, M.G., and M. Henrion. 1990. Uncertainty: A Guide to Dealing with Uncertainty in Quantitative Risk and Policy Analysis. New York, NY, Cambridge University Press. http://www.cambridge.org/ca/academic/subjects/psychology/cognition/uncertainty-guide-dealing-uncertainty-quantitative-risk-and-policy-analysis?format=PB#Bpr6zZEm7GJRYEj7.97

- Ostrom, E. 2015. Governing the commons: The Evolution of Institutions for Collective Action. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. http://www.cambridge.org/gb/academic/subjects/politics-international-relations/political-theory/governing-commons-evolution-institutions-collective-action-1?format=PB#z7jWBPCDUjKKrpOu.97

- Walters, C.J. 1986. Adaptive Management of Renewable Resources. New York, NY, MacMillan. http://pure.iiasa.ac.at/id/eprint/2752/1/XB-86-702.pdf