Our Story

Every great organization starts with a great story, and ESSA is no exception. Born in the 1970s at the crux of the environmental movement and the renaissance of environmental management science, where we came from influences the work we do today.

ESSA Timeline:

ESSA’s roots extend back into the 1960’s and 1970’s as the offspring of two complementary but sometimes quarrelling environmental management world views: 1) expanding environmental awareness and policies; and 2) the growing application of rigorous systems analysis to ecosystems, including humans. Let’s call them Green and Blue. Some heroes will emerge in this story to calm the quarrelling and find a creative path forward, so please read on.

The Green Parent accomplished a huge amount during a short decade. The publication of Silent Spring by Rachel Carson in 1962, and an oil spill in Santa Barbara in 1969, inspired an environmental movement that led to a creative surge of environmental concerns, conversations and policies. We look back now in retrospective amazement that during the period from 1964 to 1970, the U.S. federal government passed the Wilderness Act, National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act, a greatly improved Clean Air Act, and the Clean Water Act. These are all landmark pieces of legislation, which improved the way we plan and operate our societies. In 1972 the United Nations held the first global environmental conference in Stockholm, concluding with a declaration of common principles to “inspire and guide the peoples of the world in the preservation and enhancement of the human environment”. Canada listened to the Green Parent, and in 1973 agreed to screen all development projects initiated by the federal government for their potential environmental impacts.

Meanwhile, the Blue Parent was busily taking ecological experiments and scientific understanding beyond the field and lab into simulated worlds on the computer. Pioneering Blue Parents included Howard T. Odum (who applied systems theory to ecosystems), Donella and Dennis Meadows (and co-authors), who modelled the world’s economy and environment for the 1972 book Limits to Growth, and C.S. “Buzz” Holling, who in 1973 synthesized an enormous number of studies for his paper on the Resilience and stability of ecological systems.

The quarreling between Green and Blue started in the early 1970’s. To comply with environmental regulations, Green produced voluminous environmental assessments (EAs), with long lists of species found in the project area, checklists of which actions might affect which species, and tenuously worded predictions of environmental impact. Blue would shout: “The EA Emperor has no clothes! You have no empirical evidence, rigorous science and systems analysis to support your conclusions regarding environmental impacts; there are enormous uncertainties; and your EAs don’t help decision makers!”. Green would reply: “I’m doing my job the best I can – you’re not much help!”. Environment Canada intervened as a quasi-marriage counsellor from 1974 to 1976, funding a series of focused case studies to stimulate dialogue and synergy between environmental managers and scientists, and determine if systems analysis could improve EA practice. Five-day workshops were held at the University of British Columbia (UBC) and the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis in Laxenburg, Austria (IIASA), with exploratory simulation models used to integrate system understanding and focus the conversation on critical uncertainties affecting decisions.

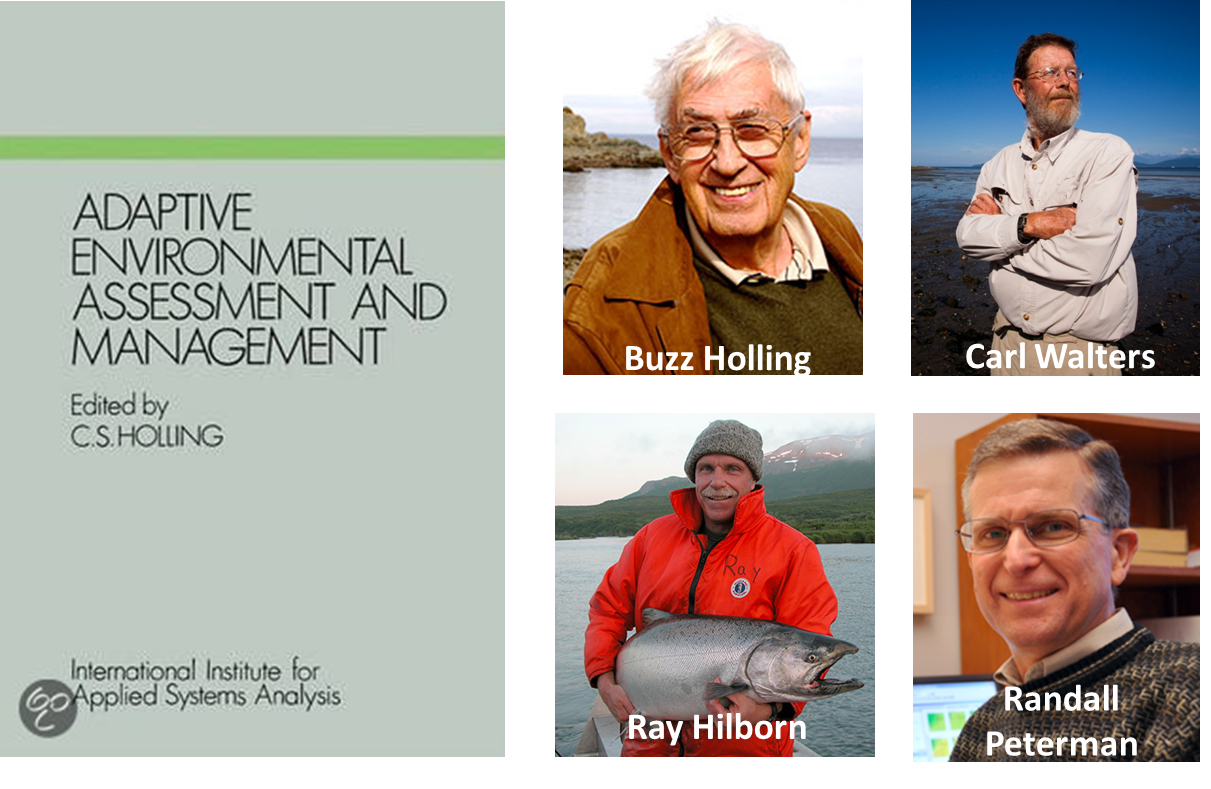

These case studies were merged into a 1978 book called Adaptive Environmental Assessment and Management (AEAM), edited by Buzz Holling, with key contributions from Buzz, Carl Walters, Randall Peterman and Ray Hilborn. The book had an exceptionally boring grey cover, and was known affectionately for decades afterwards as “The Grey Ghost”. But inside was a rich trove of valuable concepts and methods, the birth of the principles and practices of adaptive management, as well as stimulating explorations of human-ecosystem resilience. At its core, AEAM involves embracing uncertainty, applying both rigorous science and systems analysis to understand environmental problems within dynamic ecosystems, and deliberately designing contrasting actions and associated monitoring so as to learn over time. These authors attracted a number of similarly minded and talented graduate students, who soon were trained to run workshops, build models, and lead focused conversations between managers and scientists. Three of these grad students (Bob Everitt, Nick Sonntag, Mike Staley) found an administrator named Joan Anderson, and on November 1, 1979, created ESSA Environmental and Social Systems Analysts, a double ESSA acronym.

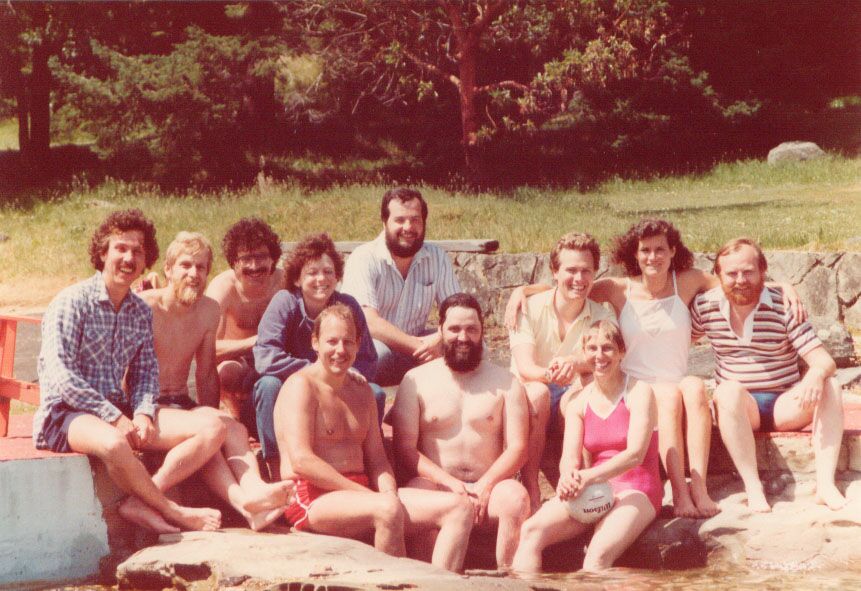

The three founding members of ESSA soon recruited a bunch more staff, primarily from the UBC farm team: Mike Jones, Dave Marmorek, Peter McNamee, Tim Webb, Pille Bunnell and Lorne Greig. The early days of ESSA were an exciting time. We’d run 5-day workshops, often staying up all night to get a model working (sort of), and then blearily lead managers and scientists to explore the pretend world we had jointly created, stimulating conversations about what they needed to do in the real world, especially the idea of using contrasts and management experiments to reduce key uncertainties. We’d tackle any problem with great enthusiasm, work extremely hard, fully admit our ignorance, challenge everyone’s assumptions including our own, and catalyze creative ways to rethink old problems. We tried to meld Green and Blue. Most of our projects focused on the management of forests, wildlife, lakes and rivers, arid lands or fisheries in in North America. At times our model predictions would go wildly astray, most famously the 1200 kg lake herring which grew in an ESSA model of a lake in Algonquin Park. Fortunately, our clients seemed to remember our energetic enthusiasm and systematic approach more than our mistakes. We’d occasionally have retreats at Yellow Point Lodge on Vancouver Island to ponder what we’d learned from our many projects across North America and Asia, how to adjust our methods, and what new things excited us. The processes and methods of AEAM began to evolve, using conceptual models and impact hypotheses in addition to simulation models, better integrating models with monitoring data, and building models through a slower, more careful process (rather than error-prone, all night coding sessions)

ESSA in 1983 at Yellow Point Lodge: Back row – Bob Everitt, Tim Webb, Dave Marmorek, Gina Cunningham, Mike Staley, Mike Jones, Jean Zdenek, Lorne Greig. Front row – Nick Sonntag, Pete McNamee, Pille Bunnell.

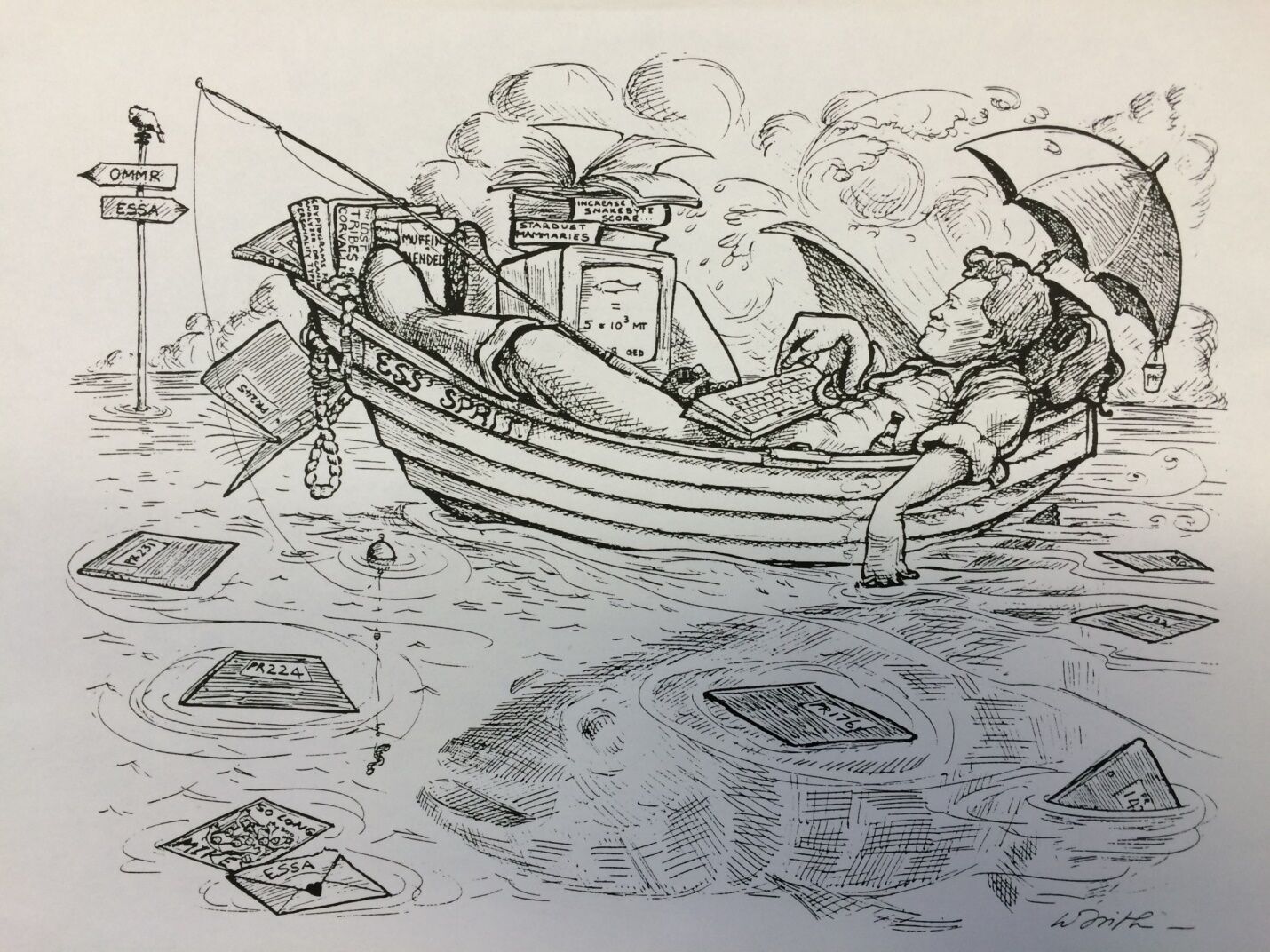

Mike Jones leaving ESSA for the Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources in 1988, happily simulating a very large lake herring.

ESSA grew in multiple dimensions, adding more people and applying the principles of AEAM to a wider range of problems. These included industrial and urban pollution in Asia, the effects of multiple pests on forest management, the impacts of energy facilities and other factors on fish populations, the design of very large scale monitoring programs, and the role of carbon and climate change in forests. While AEAM remained at the core of our practice, we diversified the tool box we’d use for different challenges, including both expert systems and decision analysis. We learned that each environmental problem and set of institutions required a unique set of processes and strategies, and developed more shades of Green and Blue to add to our palette of paints. We were extremely fortunate to work with many talented managers and scientists in government, non-government and private organizations. These clients and colleagues became part of our larger learning community, deepening our insights about ecosystems and people, and allowing us to both learn and make a positive difference in the world.

Our growing reputation has created opportunities to apply AEAM principles to environmental assessments, ecosystem restoration and species recovery programs in many parts of North America, and to EAs and climate adaptation plans in Latin America, Asia and Africa. Work in developing countries involves building capacity in both communities and agencies, and carefully selecting tools and assessment procedures that can be sustained over the long term. Some of our most meaningful projects have included work to recover fish and wildlife populations in the Columbia, Okanagan, Trinity, Rio Grande, Platte and Missouri River basins. In some cases we’ve been fortunate to see multiple iterations of the AEAM cycle: assessing problems, designing implementation and monitoring plans, implementing those plans, seeing significant improvements, learning, and adjusting both hypotheses and actions.

As we deepen our understanding of problems, we see the need to increasingly merge multiple streams of knowledge to help clients, communities and ecosystems: environmental assessment, adaptive management, ecological science, and climate change adaptation. We remain closely associated with both UBC and Simon Fraser University, serving as adjunct professors to bring our real-world experiences to faculty and graduate students, and working collaboratively with them on many projects. Our commitment to this beautiful Green and Blue planet, and its inhabitants, remains as strong as ever.

The latest ESSA family portrait.