Utilizing M&E to Maximize Children’s Participation in Community-Based Adaptation

Jimena Eyzaguirre

International Team Director | Climate Change Adaptation Lead . Bio | in

Last year I worked with Plan International to evaluate the pilot phase of their child-centered climate change adaptation (4CA) project implemented in Indonesia, Laos, Thailand and Vietnam between 2011 and 2014. Children are often more vulnerable to impacts of climate change than adults. Plan considers it important for girls and boys to contribute to and benefit from community adaptation plans and decisions.

Working on this final evaluation made me reflect on the role of M&E in harnessing lessons about what enables households and communities to take action to reduce climate vulnerability and in what contexts. Evidence on the translatability of successes in 4CA beyond niche examples or of its sustainability when project funding ends remains weak (Mitchell and Borchard, 2014). Drawing from complexity concepts and developmental evaluation practice, here are some preliminary ideas and suggestions to contribute to the evidence base.

How can we generate recommendations for scaling (child centred) climate change adaptation / resilience programming in the region and beyond?

1. Distinguish complex from simple or complicated

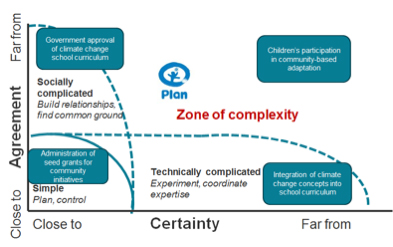

Plan’s goal with the 4CA project was to support “safe and resilient communities in which children and youth contribute to managing and reducing the risks associated with changes in the climate”. Project activities ranged from developing and disseminating information and educational materials, to facilitating community-led action planning, to providing seed grants to fund locally-appropriate climate-smart solutions to training youth in participatory video as an advocacy tool. These activities varied in complexity (see examples in figure below).

Why distinguish between simple, complicated and complex? With simple and complicated situations, results chains are straightforward and outcomes are predictable (Zimmerman, Lindberg and Plsek, 1998). Good practice and replication fit with the simple and complicated. Plan’s 4CA pilot project supported district-level and national roll-out of climate change and disaster risk reduction curriculum for schools to great effect. Those project components are complicated and scaling by replication could be appropriate in this case.

Why distinguish between simple, complicated and complex? With simple and complicated situations, results chains are straightforward and outcomes are predictable (Zimmerman, Lindberg and Plsek, 1998). Good practice and replication fit with the simple and complicated. Plan’s 4CA pilot project supported district-level and national roll-out of climate change and disaster risk reduction curriculum for schools to great effect. Those project components are complicated and scaling by replication could be appropriate in this case.

For complex situations – such as furthering child-centred community-based adaptation – the concept of core principles is useful (Patton, 2011).

2. Identify and test core principles

Core principles capture the essence of an intervention and guide scaling decisions as the intervention is adapted to different contexts (see Shared Assets, 2014, for a good summary of strategies for scaling). For the 4CA pilot project evaluation, we tried to tease out core principles by exploring patterns of stakeholders’ perceptions on the value-added and uniqueness of the project relative to others. We found that project stakeholders (that we interviewed) value process attributes of 4CA above all else (e.g., intergenerational, responsive to needs of direct beneficiaries, attentive to most marginalized). With further inquiry and testing through ongoing M&E plans and implementation, these findings could translate into core principles.

How can we generate evidence so interventions can meaningfully contribute to climate change adaptation and enhance other development aims in the short term?

1. Adopt practices from developmental evaluation

Our evaluation revealed the tradeoffs Plan managers face in promoting children’s participation in designing and implementing local climate-smart solutions and meaningfully contributing to community adaptation. Truly child-led initiatives tended to be about environmental awareness not climate change adaptation.

Developmental evaluation (DE) offers structured ways of collecting data and directing reflective practice to assess the benefits of 4CA and maximize both children’s participation and adaptation outcomes (Gamble, 2008, gives a DE 101). Among the first steps in DE is establishing an “inquiry framework” that facilitates judgment about what is being developed, what is and isn’t working and what to do next (Patton, 2006). The task is then to track, monitor and provide continuous feedback to program managers on what emerges. Entry points for DE practice include routine program monitoring, internal evaluation activities, action research, annual reflection meetings and external evaluations.

2. Be sure to match your focused inquiry to the situation

Inquiry frameworks can adopt many lenses so it’s important to match the framework to the situation (Patton, 2011). As an example, the inquiry framework we suggest for Plan’s 4CA project is values-based and promotes learning about the interaction between children’s participation, progress on community adaptation and Plan’s contribution to this change. For example, questions could include:

- What are the priority values that will guide how Plan engages project stakeholders on 4CA? How do we know whether we are living out our values? How do our values inform program developments?

- What specific, substantive lessons can be drawn on the relationship between children’s agency and communities’ engagement in adaptation? How do these relationships change over time, with what consequences?

The suggestions provided here relate to Plan’s 4CA project but could well apply to other interventions supporting social change. What experiences do you have in developmental evaluation in the context of community-based adaptation? What kind of analysis have you done to support recommendations on scaling up or out?

For further reading:

- A. Dinshaw et al. (2014). Monitoring and Evaluation of Climate Change Adaptation: Methodological Approaches, OECD Environment Working Papers, No. 74, OECD Publishing.

- B. Zimmerman, C. Lindberg and P. Plsek. (1998). edgware: insights from complexity ideas for health care leaders. Irving, TX, VHA

- J. A. Gamble. (2008). A Developmental Evaluation Primer. Montreal, The J.W. McConnell Family Foundation.

- M. Patton (2006). Evaluation for the Way We Work. The Non-Profit Quarterly, 13, 1, 28-33

- M. Patton. (2011). Developmental evaluation: applying complexity concepts to enhance innovation and use. New York, The Guildford press

- P. Mitchell and C. Borchard (in press). Mainstreaming children’s vulnerabilities and capacities into community-based adaptation to enhance impact. Climate and Development.

- Shared Assets (2014). Scaling Land-Based Innovation: A Thought Guide To Growing Innovations Well.

This post originally appeared online as part of Earth-Eval’s blog series: https://www.climate-eval.org/blog/using-me-maximize-children%E2%80%99s-participation-community-based-adaptation